If like me you find scalar playing somewhat boring and tedious, triad pairs offer an interesting alternative. This approach places more emphasis on intervals rather than scales, using triads as building blocks.

What are triad pairs?

In music theory, particularly within jazz and contemporary improvisation, triad pairs are exactly what you’d expect: a pair of triads used together to generate melodic lines.

Rather than relying heavily on traditional seven-note scales, which can sometimes sound too linear or predictable, triad pairs offer a way to break out of that “scalar” playing by organizing notes into wider, more angular relationships that still sound inherently structured and melodic.

The Core Concept: Mutual Exclusivity

To get the most out of a triad pair, choose two triads out of a scale that do not share any notes. By not sharing any notes, the two triads are referred to as being mutually exclusive.

Because a triad has three notes, combining two mutually exclusive triads gives you a total of six distinct notes creating hexatonic scale (i.e. a scale consisting of 6 notes). By limiting your note choices to these six notes and moving back and forth between the two triads, you can create lines with a distinct, modern sound.

An example process

The process I am going to work through is based on identifying the parent scale and building off that. However, there are alternative approaches, which I will mention at the end.

When I’m learning something like this, I like to work in familiar territory. This is probably a failing of mine, but for the purposes of this post it will help me put things in context. So I’m going to start with the notion that I’m going to be improvising over an Am7 chord, and build the triad pair accordingly.

Step 1 – Identify the parent scale

First, we need to know what notes are available to us. Since Am7 is the ii chord in G major, the scale mode we are dealing with is A Dorian (the second mode of G major scale). This gives us the following notes:

A – B – C – D – E – F# – G

Step 2 – Build the diatonic triads

Build basic triads (root, 3rd and 5th) off of each note in A Dorian:

- i: A minor (A, C, E)

- ii: B minor (B, D, F#)

- III: C Major (C, E, G)

- IV: D Major (D, F#, A)

- v: E minor (E, G, B)

- vi°: F# diminished (F#, A, C)

- VII: G Major (G, B, D)

Step 3 – Find a suitable pair of triads

Look at the list of seven triads and find two that fit the following two rules:

-

They must be mutually exclusive (no shared notes).

-

They should outline the chord tones (of Am7 in our example) plus some extensions.

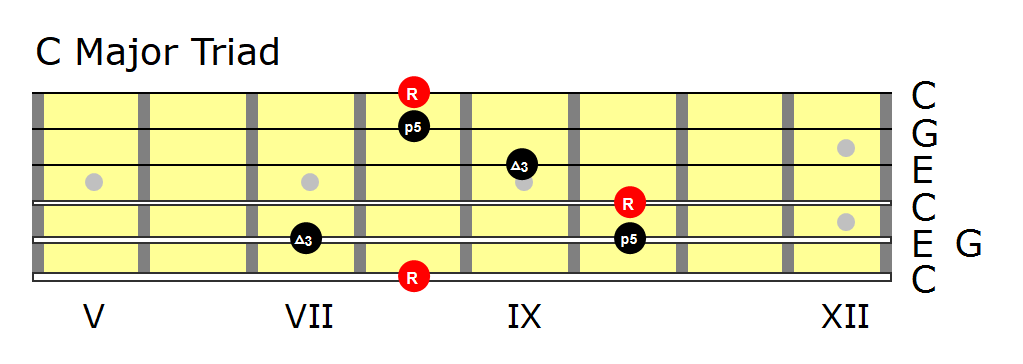

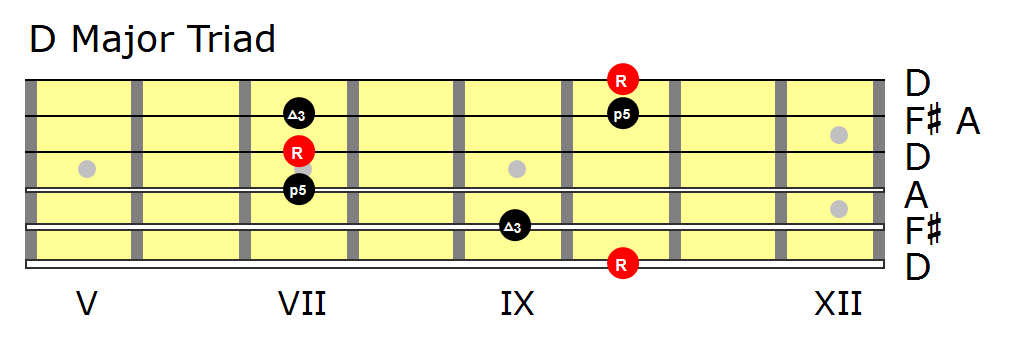

Let’s look at the two major triads right in the middle: C Major and D Major.

- C Major: C, E, G

- D Major: D, F#, A

Do they share notes? No, they do not so they are mutually exclusive. We have satisfied the first rule.

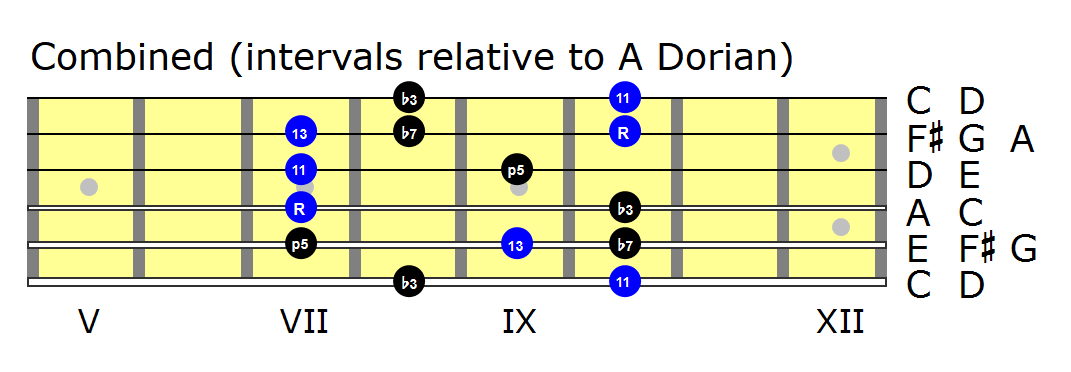

Relative to the original Am7 chord we want to play over, this collection of notes gives us the following intervals:

Root - b3 - 4 - 5 - 6 - b7

Or written another way:

Root - b3 - 5 - b7 - 11 - 13

So that’s the chord tones of Am7 plus 2 extensions, 11 and 13. We have satisfied the second rule. Nice!

Note that the root notes of the two triads – C and D – are the 4th an 5th of G major, the parent scale of A Dorian. Some people take this as a rule: identify the parent scale (G major in this case) and use the 4th and 5th to build major triads. Those two triads are your triad pair. This would apply to any scale type, including melodic or harmonic minor scales.

Other people regard the process as more flexible giving more than one pair to choose from. For example, if we want a softer sound without the bright F# (13th) we could look at the list of triads and pick:

- G Major: G, B, D

- A Minor: A, C, E

They are mutually exclusive and give us the Root, 9th, b3, 11th, 5th, and b7. It’s a slightly darker, more “inside” sound than the C/D major pair, but completely valid.

However, the 2 major triads on the 4th and 5th of the parent scale is a good starting point.

Alternative approaches

Alternative Method 1: The “avoid note” shortcut

Educators like Jens Larsen often teach triad pairs by working backward from the “avoid notes” (notes in a scale that painfully clash with the underlying chord). This is a jazz-oriented approach where avoid notes are a key concept.

Instead of writing out all seven diatonic triads, you do this:

- Identify the parent scale.

- Identify the one note in that scale that clashes with the chord (the avoid note).

- Remove it, and build your two triads on the two scale degrees immediately following the removed note.

Alternative Method 2: The “formulaic” approach (Weiskopf’s Method)

Saxophonist Walt Weiskopf completely ignores parent scales in his teaching. He teaches triad pairs as memorized intervallic formulas, specifically focusing on pairs of identical triad types (like two major triads separated by a whole step).

Instead of calculating scales, you just memorize the root-relationship formula for the chord type you are playing.

| Chord Type | The Formula | Example in G Major | Resulting Sound |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minor 7 | Two Major triads on the b3 and 4 | C Major & D Major over Amin7 | Modern Dorian |

| Major 7 | Two Major triads on the 1 and 2 | G Major & A Major over Gmaj7 | Bright Lydian |

| Dominant (sus) | Two Major triads on the b7 and 1 | C Major & D Major over D7 | Mixolydian / Sus |

| Altered Dom | Two Major triads on the b5 and b13 | Ab Major & Bb Major over D7alt | Tense, Altered |

Exercises

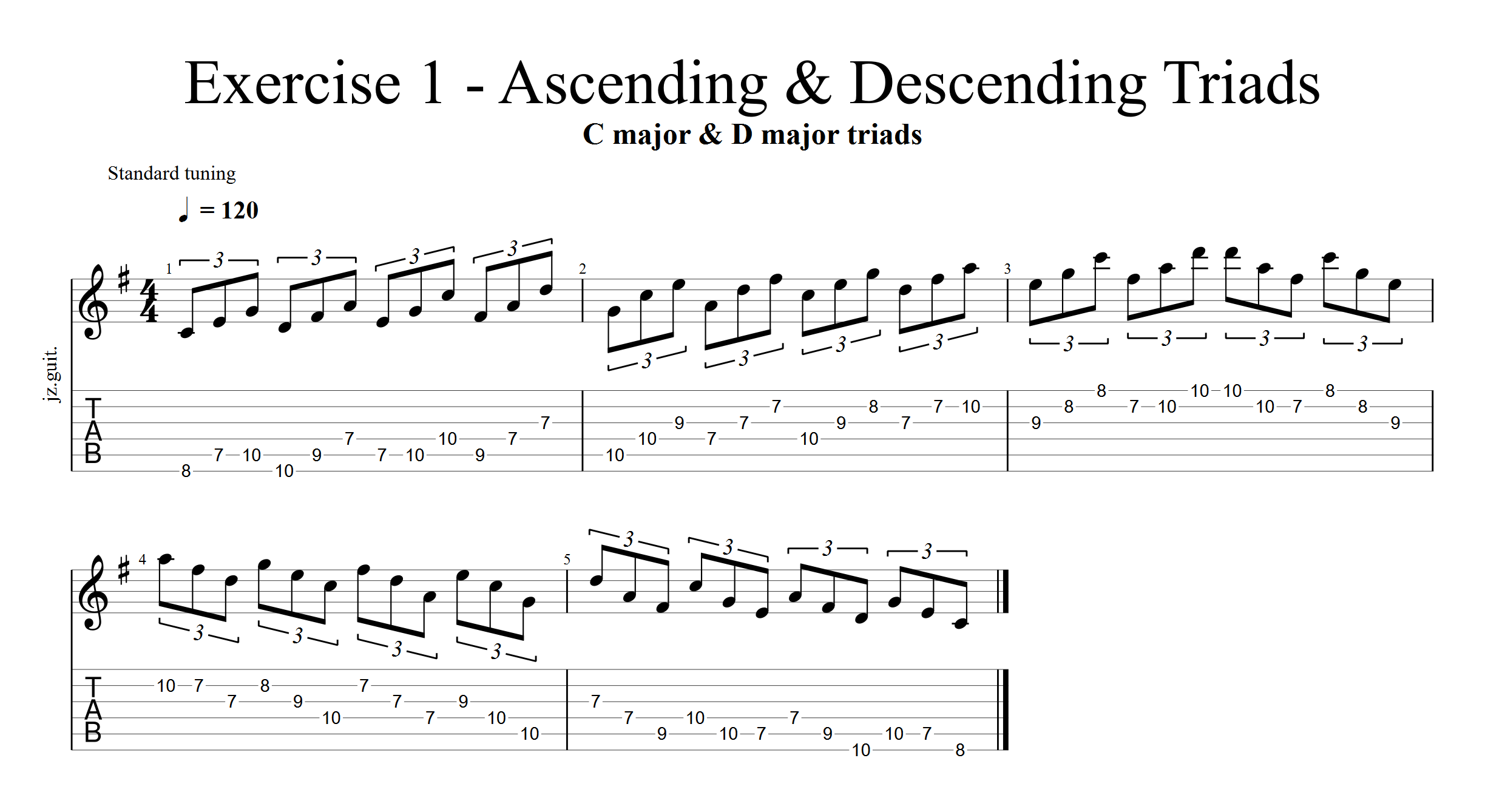

Now you can come up with some exercises to get these under your fingers. Here’s one to get you started. It’s just playing the triads with an ascending pattern, playing 3 notes of the C major triad followed by 3 of the D major triad, then repeat descending.

Try different note combinations, and consider 4 note groupings rather than triplets to avoid getting stuck in the triplet vibe. And of course there’s the whole fretboard to cover.