This post covers a bit of ground including how we create forward motion in music, how we harmonise the minor ii-V-i chord progression, and secondary dominants. All this from a look at ii-V-I progressions found in Autumn Leaves.

One of the ways we can create forward motion in music is through root movement. In general, root movement can be characterised as either strong or weak and to create strong forward motion in music utilising strong root movement will help. Strong root movement can be created in the following ways:

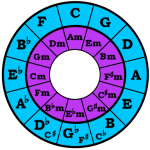

- The strongest root movement can by created by moving backwards through the cycle of 5ths (sometimes called back-cycling).

- The next strongest form of root movement is by moving a semitone, either up or down.

- The final form of strong root movement is by moving a tone, again either up or down.

Looking at ii-V-I

Take the classic ii-V-I progression as an example. In Bb major that would be Cmaj7 – F7 – Bbmaj7. If we compare that with the cycle of 5ths we can see that we have moved backwards (C to F to Bb).

Take the classic ii-V-I progression as an example. In Bb major that would be Cmaj7 – F7 – Bbmaj7. If we compare that with the cycle of 5ths we can see that we have moved backwards (C to F to Bb).

Equally interesting is what happens when we compare this with chord families. The ii chord is in the Subdominant family, the V chord is in the Dominant family and the I chord is in the Tonic family. So, you can see that ii-V-I follows the basic rules of forward motion through use of chord families; Subdominant leads to Dominant leads to Tonic.

This all helps explain why the ii-V-I progression is so prevalent; it obeys the rules of harmonic motion laid down by chord families as well as creating strong root movement by back-cycling through the cycle of 5ths. A double whammy!

But what about the minor ii-V-i?

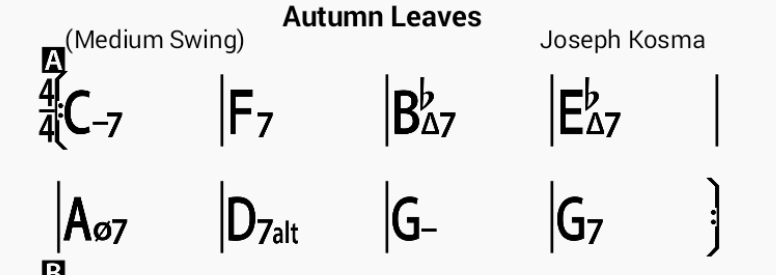

Take a look at the first few bars of the jazz standard Autumn Leaves in Bb major.

It starts with a major ii-V-I (the first 3 chords) and follows the rules we’ve already established about chord families and strong root movement. We have a Subdominant chord leading to a Dominant chord leading to a Tonic chord. The root notes are also back-cycling through the cycle of 5ths (C to F to Bb).

The next chord is a IV (Ebmaj7) which links into something that looks like a ii-V-I except it’s in a minor key (Amin7b5 – D7alt – Gm). It’s actually a ii-V-i in G minor, the relative minor of Bb major.

At first look the voicings used in a minor ii-V-i progression appear to be a strange having a m7b5 and a Dom7alt. The reason is that in a minor key we don’t harmonise against the same intervals we’d get from the relative minor of a major key. If we did that we’d be using the notes of the Natural Minor (or Aeolian mode). Instead, when harmonising in a minor key, we use a different scale: the harmonic minor scale.

The Natural Minor (or Aeolian mode) has the following intervals:

R – 2 – b3 – 4 – 5 – b6 – b7

The Harmonic Minor by contrast has the following intervals:

R – 2 – b3 – 4 – 5 – b6 – 7

You can see they are pretty much identical except we raise the b7 of the Aeolian mode to a major 7.

But why do this? Well, it has been known for a long time in schools of Western music that the Natural Minor scale doesn’t harmonise well – it just doesn’t sound good – so over time things were tweaked to sound better. The result was the Harmonic Minor scale.

The result of this is that whereas the chords in a major ii-V-I are strictly diatonic (giving us m7-dom7-maj7) we follow a different formula for a minor ii-V-i:

- m7b5

- Dom7 altered

- Any minor chord (e.g. minor triad, min6, min/maj7 etc.)

Looking at Autumn Leaves we have Amin7b5 – D7alt – Gm in bars 5 to 7. This is a minor ii-V-i in the key of G minor and if we harmonise using the Harmonic Minor scale the Am7b5, D7alt and Gm chords are the result.

Note also that the D7alt contains a tritone between the 3 and b7 (Gb and C) creating harmonic tension that wants to be resolved. This is done by moving the Gb to a G which takes place when we move the D7alt to Gm. You can also see that the root notes of the 3 chords (A, D and G) are back-cycling through the cycle of 5ths. We have strong forward motion again!

A final point. What’s the G7 in the last bar for? Well, this is an example of a secondary dominant. You can see this post for a brief explanation.

You can see why Autumn Leaves is such a useful teaching tool. It contains good examples of how to use chord families, strong root movement by back-cycling through the cycle of 5ths, and examples of major ii-V-I and minor ii-V-i chord progressions.